Jane Ripley McGuinn, January 13, 1911-December 5, 2012

My remarkable grandmother died last week. She was almost 102 years old, and she was ready. She’d told us that she did not want ever to return to the hospital and so she died in her own bed, at about 2 am, with my Aunt Molly by her side. It’s what she wanted, and while we’ll all miss her, it was time. It was actually more than time.

She was a mythic figure, our “Mommy Jane” — a name my eldest cousin Brad gave her. She raised Brad from infancy to about four. When he was learning to speak, he called her Mommy. When corrected, he called her Jane. When corrected again, he put the two together, and Mommy Jane she became. After a while it’s what everybody called her. Older men in feed caps, in her small Illinois farm town, called her “Mamma Jane.”

She was born into wealth in Chicago. Here she is with the Water Tower in the background — a photo that was taken in the middle of what is now Michigan Avenue. She lived a few blocks away, and grew up attending Francis Parker School, then Northwestern University. She was much loved by her parents, and had a deep connection with and love for her uncle, Charles A. Plamondon Jr., known as “The Colonel.” Their correspondence through both World Wars fills boxes, and she told me in her early 90s, he that he had been her “very special person.” From what I can tell, he is the one who encouraged her love of horses and riding, for he led the cavalry regiment in Chicago, and often allowed her to come ride with his men.

The family spent winters in Chicago, and summers on the family farm that her great grandparents had built in the late 1860s in Leland, about 90 miles southwest of the city. When she was just a toddler, her grandparents, Charles Ambrose Plamondon and Mary Makin Plamondon died on the Lusitania. When she was in her early 90s, we went through boxes of photos together — I wanted to get the names straight so that when she was gone they wouldn’t just be a mystery. In one box we found all sorts of Lusitania stuff — the settlement papers, condolence notes. There was a note from some people in Helena, MT that nearly broke my heart. They were outfitters, who had apparently guided my great-great grandparents several years running when they had come out to Yellowstone — we couldn’t find the photos that evening, but apparently there’s a whole box of them showing them “camping” in Yellowstone in wall tents, and eating at tables set with proper linens and silverware. Aside from all that, they must have been lovely people, because when it hit the papers that they’d been on the ship, the folks who ran the outfitters wrote a heartbroken, lovely note.

She had one younger brother, Bradford, with whom she appears to have had a wicked case of sibling rivalry. Bradford married Barbara Cox and died only months later, flying in World War II, leaving a very young war widow who subsequently went on to build, with her sister Anne, Cox Industries.

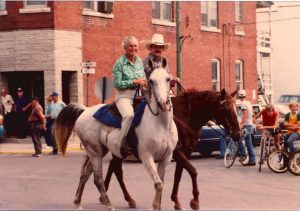

Horses were my grandmother’s passion, she rode in every horse show she could, for anyone who would give her a mount. She told a story about Mr. Augustus Busch sending her 12 dozen American Beauty roses when she won for him one time. “Such a waste,” she said. “We loaded them up in the red wagon and took them to all the hospitals.” Continuing the story she told me that she much preferred riding for the Bronfman’s because they “gave me tack when I won. Something I could actually use.” She hunted out in Wheaton and became a great favorite of Mrs. McCormick — an odd family connection that Jim Fergus, the novelist and I, discovered many years later when we met at a book event (his grandmother married a McCormick).

She was a very talented polo player who was denied the opportunity to play at a competitive level because of her gender, an injustice that made her livid until the very end. She could play practice matches, but couldn’t compete in “real” matches. While this seems arcane now, in her prime 30,000 people took the train out to Lake Forest in 1933 to watch Will Rogers and his team beat Tommy Hitchcock’s team from the east coast. It was a huge public sport from which she was barred because she was a girl.

She was also, according to family lore, offered a scholarship to Northwestern Medical School, a scholarship her father refused to let her accept, telling her she’d be taking a livelihood away from a man who would need it to support a family. When I was young, she was adamant that I would be whatever I wanted, that girls could do anything boys could, that I should travel and be independent and have my own money. As an old woman, she’d look at me and shake her head. “I don’t know why any of you girls would get married,” she’d say. “Now that you don’t have to.”

She married John Carroll McGuinn in 1934. That night we were going through photos, I tormented her some by reading aloud the society page write ups of her wedding. “The wedding of the season” they all said it was. “Oh pooh,” she replied, using her favorite epithet, “we were the first people married after prohibition ended.” They left that same night for San Francisco, and settled in Burlingame, where her oldest two children, Mike and Lynn were born. She was an energetic, if not always particularly attentive mother — when she told us how she used to put Mike down in his baby buggy for a nap on the back patio, then go play 9 holes of golf, we teased her that she’d be put in jail these days. “He was fine,” she said. “I left the dog watching him.”

After four years in California, they moved back to Chicago and had my mother Joan, and my aunt Molly. My grandmother went to work at Francis Parker School in 1946, both because she was a woman who had too much energy to happily stay at home, and because my grandfather had developed a drinking problem that cost him his job. She put all four of her kids through Parker by working in the office, driving the school bus, coaching field hockey and generally bossing everyone around. She retired for the first time in 1968 — which I remember because my cousin Brad and I had to walk out on the big stage in the auditorium where we presented her with a small black dog she named Francis. She returned to Parker in the 1980s, when she came to live with my Aunt Molly, who has been teaching there since the late 1970s. She stayed at Parker until she was in her early 90s, when she moved out to the farm full time. Occasionally I run into people who attended Parker, and everyone knows and remembers her, some fondly, some not so much. There’s one man I met at a party here in Livingston, who remembers her catching him sliding down a bannister, then pulling him off and giving him what for — he’s older than I am by a couple of decades, but still remembers, all these years later.

After she retired from Parker the first time, she had a period of financial and personal independence that defines the woman all of us cousins knew and loved. She travelled with the Chicago Farmers Association to both the Soviet Union, and twice, to China. She was part of one of the first American delegations into big China, and I wish I had them, but there are two photos of her at the Great Wall. She hated to walk, and the first time she went to the Wall, she spied a guy with a donkey. She paid him to let her ride the donkey up the steep path to the Wall. When she returned to China several years later, he had a concession taking tourists up the wall with his donkey, and there’s a second photo of the two of them laughing about how she brought a little capitalism to the Great Wall. She was amazed by real Chinese food on those trips, and when she came back, she found a small Chinese restaurant in Dekalb, Illinois that she loved. She took her photos of herself at the Great Wall, told them her stories, and they cooked off the menu for her. Fifteen years later, my best friend from college married a Chinese man from Hong Kong. His brother came to Fort Collins for the wedding, and it turned out he ran a Chinese restaurant in Dekalb — when I asked, it turned out that Christopher was indeed the same man who had been feeding my grandmother for a decade or so! It’s my favorite small world story.

It was during this time period that she joined the Michigan Trail Riders Association and twice a year, until the mid 1980s, she trailered a horse up and rode across the northern part of the state with her friends. The photo at the top of this post is from 1963, the first year she joined, with one of her favorite horses, Fancy Annie. We were always the only kids we knew whose grandmother drove a pickup truck with a camper on it, and rode and camped her way across Michigan every year. She also fell in love with snowmobiling, and used to drive up to Michigan to snowmobile with her trail riding friends.

She broke a leg snowmobiling one winter — chasing someone through the woods in a snowstorm (made even more challenging because she’d lost the sight in one eye in an accident in the early 1960s, so she didn’t have any depth perception). She came to live with us that winter. Our father had bought us ponies, which since my youngest brother Michael was ill with the cancer that would kill him the following summer, no one had had time to teach us to ride. Every afternoon after school, Mommy Jane would stump out to the barn with us on her crutches, one leg in a full cast to the hip, and teach us to groom and tack up. Then she’d set us to walking up and down the barn aisle, doing old-fashioned cavalry exercises like toe touches and “around the world.” We didn’t really learn to ride that winter, but we did develop pretty good seats from just fooling around and getting comfortable.

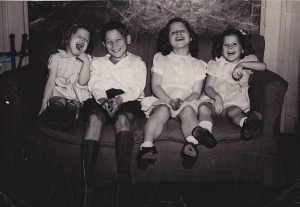

There were, eventually, nine of us cousins, and we all spent a lot of time on her farm in Leland, where we were raised more like siblings than like cousins. This is the Donahue, McGuinn and Freeman cousins (my Aunt Lynn had three kids — Jennifer, my only other girl cousin, Matthew and James who weren’t there for this visit). Somewhere she’d gotten a deal on a gross of the wooden slats they use for pants hangers — and we’d spent the whole weekend building an office complex, complete with landscaping. As we finished, she let us pick from her much-protected collection of Matchbox cars to fill the parking lots. Those Matchbox cars, she had a ton of them — we used to joke with her that when she went, that was the first thing we were all going to seek out in that house.

Being sent to Leland was always an adventure. For one thing, Mommy Jane didn’t really cook, and since her kitchen hygiene was, shall we say, lax, food poisoning was always a risk. The up side was that at Mommy Jane’s, there was an abundance of the kinds of processed food our mother didn’t let us eat — Hostess products, “astronaut sticks,” those individual-sized boxes of Kelloggs cereals, including the sugary ones. Oh, and Kentucky Fried Chicken, which opened two towns over, and was a staple. For Mommy Jane’s 100th birthday we had KFC, a small chocolate cake, and ice cream. It was perfect.

Food issues aside, adventure and creativity were always on deck when you were with Mommy Jane. I have a distinct memory of her arming us all out of the closet underneath the stairs in the front hall. Like some figure out of an old-time Western, she handed out beebee guns to all of us, Brad, Rip, me, Patrick, Adam and Jason, and sent us outside to shoot tin cans off the old rebar sticking out of what had once been the sheep barn. We all got outside and had a powwow — Jason was about three at the time, and he hadn’t quite mastered walking without tipping over. As a group, we decided that maybe Jason shouldn’t have a gun. Of course, of all of us, Jason is the only one ever to have had a shooting accident (minor, in his early teens) while Rip went on to be a nationally-ranked trap and skeet shooter, and now runs the SWAT team for the Honolulu FBI office.

In her last couple of decades, she settled in Leland where, to keep herself busy, she started a free lending library in 2003. Someone she knew bought an old school building and agreed to heat it, and with donations left over from the annual Francis Parker book sale, she had quite an inventory. The Ottowa paper did a story on her that’s archived here, although unfortunately it doesn’t have the photos. She did it up, just like a real library, inventorying books on an old clamshell Mac, sorting them by topic and alphabetizing by author. She ran it until 2009, when her health declined to the extent that she just couldn’t get down there any more.

She was a fierce, energetic, complicated person about whom I’ve written here and here and here for starters (there’s more if you really want, just type “grandmother” in the search box). My cousin Jennifer and I have been talking a lot on the phone lately and while our lives are very different, we were both much loved by Mommy Jane, and encouraged and supported by her. In Jennifer, she got a granddaughter who has a loving and supportive marriage, and who has raised two wonderful girls. In me, she got the one who is financially and personally independent – the one who is happy to have a “big diamond that you didn’t even have to marry anyone for.” In her very old age, she softened up a lot. She’d say “I love you” which sort of spooked all of us for a while until we got used to it. She lived with my aunt Molly and her husband John, who did a heroic job of taking care of her, and who made sure she got her wish to die at home.

My cousin Jason, his wife Jackie, and their daughter Riley (who is the seventh generation on our farm) also live on the farm in Leland. Riley is still pretty young, but she and Mommy Jane were good friends, and she got the increasingly-unusual experience of growing up in a multigenerational household. She was an unforgettable person, and even though we all knew in our heads that at almost 102, she couldn’t live forever, we’ve all spent this week somewhat stunned that Mommy Jane, that larger-than-life character we knew and loved, could actually die.

This is just a tip of the iceberg — a portrait of my experience of Mommy Jane, as her eldest granddaughter — and I hope that those of you who knew her, who stumble across this post, will add your memories in the comments.